INTRODUCTION

WHEELS OVER INDIAN TRAILS

by Gloria Steinem

This is a very important book. It could be the most important of this new century if it were to get the mindfulness it deserves. Wilma Mankiller has brought together wise voices in a conversation about the things for which we long the most: Community, a sense of belonging in

the universal scheme of things, support from kin and friends, feeling valued as we are. Balance, between people and nature, women and men, youth and age, people of different skills and colors, past and present and future. Peaceful ways of resolving differences, sitting in a circle, listening and talking, a consensus that is more important than the time it takes. Being of good mind, a positive outlook that energizes positive words and actions. Circle as paradigm, a full range of human qualities in each of us, equal value of different tasks, reciprocity, a way of thinking that goes beyond either/or and hierarchy. Spirituality, the mystery in all living things, the greatest and smallest, and therefore, the origin of balance, a good mind, peace, community.

I suspect we are all drawn to these lifeways. They may be in our DNA from the 95 percent of human history in which they were common, before patriarchy made hierarchy seem natural. I know we are suffering without them. Kids deprived of community create gangs, adults without talking circles create conflict, people without balance “conquer” nature and so defeat themselves, and cultures without spirituality consign it to life after death. Even the liberals and conservatives who are so divided in this country-like the democrats and theocrats who are killing each other in the world-are different only in that liberals and democrats still hope to move toward these possibilities, while conservatives and theocrats consign them to an elite or another life.

Both sides should read this book. They will find evidence that the more than 500 advanced cultures on this continent before Europeans arrived-cultures that often shared values with indigenous groups on other continents-developed wisdom that has been carried on by a few people despite centuries of genocide, theft of homelands, and forced assimilation. Their mission to preserve what is often called The Way is so strong that they are willing to share it with the descendants of invaders who killed 90 percent of their ancestors with war and imported diseases. As Jaune Quick-to-See Smith says in these pages, “Culture is not race and race is not culture.” Many traditional women and men feel that the danger of the path we are now on is becoming so great that it no longer can be ignored, that they are guarding The Way on behalf of all the passengers on this fragile Spaceship Earth.

The contemporary indigenous women who speak in these pages-as well as Vine Deloria, a Standing Rock Sioux who is a professor of law, religious and political studies, and the author of important books of his own-are not describing lifeways of the past but ways of thinking and acting that are alive in the present.

You and I who are outsiders to these lifeways-who have lost our path to them on our own ancestral continents-may wonder if they are contrary to history, or even human nature. After all, our history books traditionally started when Europeans arrived, not when people evolved-a difference of 500 years versus tens of thousands. Until the 1960s, many Native Americans were forbidden to teach their own culture and languages in schools or to hold spiritual ceremonies, and their children were forced into Christian boarding schools, as if the separation of church and state didn't exist. Even now, only people who live in Indian Country, learn from traditionalists, or study the few but growing number of books like the one you hold in your hands-books that bring indigenous values into the contemporary world or document the past through handed-down stories, archaeology, and such new tools as carbon dating and DNA trails-know much of anything about the people who walked the same land that we do, saw the same mountains, harvested the same waters, and buried their dead in the same earth.

Most of us never learned that they had democratic forms of self-governance before Greece and without slavery, irrigation systems and astronomical calendars as advanced as those of Rome, and medicine using herbs and psychotherapeutic skills when Europe was relying on “humours” and leeches. We didn't know that they domesticated crops that would later save Europe from famine, cherished an oral and sometimes written body of literature, and created trade routes through what are now called Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South America. They were as accustomed to cooperation as we are to competition, as steeped in self-authority as we are in mass persuasion, as used to planning for seven future generations as we are to instant gratification, as daring in exploring inner space as we are in exploring outer space.

I could quote outside authorities on this suppressed history. For example, Benjamin Franklin and other authors of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights used the Iroquois Confederacy as one of their sources. Lewis Henry Morgan, an American ethnologist of the 1800s, documented the self-governance of the six major northeastern tribes by reciprocity, balance, consensus, and communal land ownership. His most famous book, Ancient Society, inspired Marx and Engels to aim for these goals, even in the midst of England's brutal class system and industrialization. In 1885, U.S. Senator Henry Dawes was assigned by Congress to report on the Cherokee Nation. Only fifty years after its forced relocation and massive losses on the Trail of Tears, he found that Cherokee cooperation had again created a more literate and prosperous community than the surrounding population, with schools for both girls and boys and “not one pauper in that nation.” However, this was seen as a problem. As he wrote, “there is no enterprise to make your home any better than your neighbors. There is no selfishness, which is at the bottom of civilization.” Therefore, the Dawes Act forced Cherokees to divide their communally owned land into private property.

As for Native women, suffragists regularly cited their status as evidence that women and men could and should have balanced roles. Indeed, there was no other visible source of hope in this New World where expansionism rested on the unpaid labor and uncontrolled reproduction of all women, as well as the outright slavery and forced reproduction of black women and men. In 1888, ethnologist and suffragist Alice Fletcher, who lived among the northeastern tribes, reported to the International Council of Women that, “the woman owns her horses, dogs, and all the lodge equipments; children own their own articles; and parents do not control the possessions of their children … A wife is as independent as the most independent man in our midst.” Combined with the fact that among many tribes, female elders chose, advised, and could depose the male chief and signed treaties with the U.S. government along with male leaders-and that women could divorce and controlled their own fertility though a knowledge of herbs and timing-this caused indigenous women to be seen as immoral and tribal systems to be ridiculed as “petticoat government.”

As Paula Gunn Allen, Laguna/Sioux poet and novelist, wrote in The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions, “Feminists too often believe that no one has ever experienced the kind of society that empowered women and made that empowerment the basis of rules and civilization. … the root of oppression is the loss of memory.”

This does not mean that “Indian Country” - a term for the diverse Native American community wherever it may be - should be idealized for its equality now. As you will hear from the women in these pages, it has absorbed centuries of male dominance. Yet unlike those of us who know nothing of so-called prehistory, Native women and men have a tradition of balance to bring into the twenty-first century.

Even as someone who comes from what Joy Harjo calls here the “overculture,” I have sometimes glimpsed this parallel reality. I owe this to the generosity of Native women and men who tolerated and even welcomed someone born on their land, yet raised with no understanding of its history. I'll add a few such stories here to serve as bridges for other outsiders, but I have no explanation for the odd feeling of “home” they give me. Most of all, I owe my sense of old/new possibilities to my friend Wilma Mankiller, whose great heart brings hope to everyone around her, in these pages as in everyday life.

It is 1977. Twenty thousand women are meeting in Houston for the First National Women's Conference, the culmination of a two-year process of electing delegates and raising issues from every state and territory. Because Bella Abzug and other congresswomen won public funding for this creation of an agenda by and for the female half of the nation, this meeting is probably the most racially and economically representative the country has ever seen. One evidence is the number of women from different Native tribes and nations-in their memory, more than have been able to meet together before. Along with African American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific American, and other women of color, they are forging a “Minority Women's Plank” to add to a shared agenda.

Time is short before the plenary session will vote, so they have asked me to serve as a “scribe” who collects statements from these caucuses, condenses them into shared themes, then resubmits the result for their approval. I notice that the “American Indian/Alaskan Native” caucus has poetry; indeed, “Earth Mother and the Great Spirit” are the only soaring words anywhere at this conference that is understandably focused on issues and statistics, and “hunting, fishing, and whaling” are the only references to nature. Nobody wants to lose these words, so all the caucuses decide it's okay to append individual paragraphs to the plank, thus uniqueness can coexist with unity. This allows Hispanic women to oppose deporting mothers of U.S. born children, Asian/Pacific American women to condemn sweatshops-and so on-all because Native women brought their culture with them.

As I make a last late-night round of caucuses, I notice that exhausted members seem more relaxed, even joyful. By the next day when a spokeswoman from each one reads part of this appended Minority Plank on the floor, their high spirits fill the convention hall. In a moment that delegates and journalists later describe as the high point of the conference, the whole plank is accepted by acclamation.

Afterward, the tribal women give gifts. To this day, I have my blue floral beadwork necklace in the style of the Woodlands people and my red shawl stitched with purple and gold ribbons. I wear the necklace whenever I have to do something especially hard and the shawl whenever I have the chance to dance at a powwow. Still, the most precious gift of all was that moment when 20,000 women became part of one circle.

In later years, I've often thought about this example of being unique, yet part of a community, an alternate to the either/or thinking that assumes community must compromise individualism-and vice versa. I notice that some Native parents wait to name a child until she or he does something unique, then add this name to family, clan, and tribe. At powwows, children wear miniature versions of tribal dress, not special designs or colors that would separate them from grown-ups. Everyone's tribe is easily identifiable, yet handmade regalia may be made and worn in an individual way. (Of course, blue jeans, suits, and briefcases are also Native dress, as you'll see in these pages.) In a symbolic system that is rooted in the uniqueness of plants and animals-sage for purification, the bear for motherhood, the eagle for courage, and so on-diversity is linked, not ranked. Ceremonies include a touching reference to “the two-legged and the four-legged,” a distinction without a judgment, and invoke “the four directions” and “all our relations,” meaning all living things.

Those of us who dwell only in the land of either/or-of individualism versus community, humans versus nature - have a lot to learn.

Many times a year beginning in the 1980s, I meet with the board of the Ms. Foundation for Women and other groups that now have Native American members. Our meetings always had warmth and an iconoclastic humor, but I notice that they become more so. Whether it's gentle irony about the number of white women who claim descent from “a Cherokee princess” (there was no such thing) or media questions about why Native women aren't wearing tribal regalia (for the same reason European American women aren't wearing bonnets and bustles), there is a humorous way of dealing with the daily realities of racism. From this I learn that humor and seriousness go together; indeed, the more pervasive the injustice, the greater the need for humor.

However, these new members seem bemused by the number of funding requests and discussions about sex education, lesbian rights, eating disorders, and other bodily self-esteem issues for women and girls. They look at us, their European American, African American, and Latina sisters, with kindness, as if we were new arrivals from outer space. Some try to explain that sexuality is just part of life. They illustrate this with stories of courtship and marriage customs, or of grandmothers talking around the kitchen table, or of the special places traditionally allotted to warrior women, nurturing men, and “twin-spirited” people. Others tell stories of riding ponies and playing stickball as part of valuing female bodies for what they can do, not just how they look, and the bumper stickers in Indian Country that say “Brown and Round” in whimsical defiance of a thin-and-white ideal.

I think: This easy humor and earthiness are part of what the New Age idea of Native American life just doesn't get.

I also go to sweat lodge ceremonies and discover that spirituality and humor don't have to be separate either. Prayers come in waves, as may silence or laughter, and all feel as natural together as the people themselves, from the old man seeking help from the spirits in finding a lost horse to the young woman who seeks the strength to survive AIDs. Unlike the walking-on-eggshells feeling of going to a church or temple or mosque, this is a barefoot-on-the-earth feeling of being oneself.

In the early 1990s, Rebecca Adamson, a Cherokee friend who is the head of First Nations Financial Project, asks if I want to go to a small meeting in the Badlands of South Dakota where activists will try to come up with a new financial paradigm. The idea is to add community and spiritual values to a bottom line that is otherwise only financial. As Rebecca says, “It's economics, with values added.”

During this two-day meeting, I notice something almost as amazing as the idea that success isn't just about money: The men only talk when they have something to say. For example, an Iroquois man listens for a couple of hours, then gets up to make suggestions and diagrams, then listens again. Not only does he not try to control the meeting and not try to impress the group, but he is comfortable with silence.

I realize that he has taught me something by its absence: I've been allowing well-meaning men to control meetings because I'd never experienced any other way. Of course, I've also seen Native men be as domineering as anybody else, but the point is: I've never seen a non-Native man be as comfortable with cooperation, listening, silence.

From this I learn: It's possible.

I'm not expecting any lessons about indigenous cultures to flow from the bloody break-up of the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s. In the service of ethnic hierarchy, neighbors are killing neighbors, long intermarried families are taking sides against their own kin, and rape has become a weapon of ethnic cleansing. This is all supposed to be justified as retribution for violence of generations ago.

But as Wilma and other wise friends point out, that is the lesson: They have forgotten the experience of Native Americans here, the Kwei and the San in Africa, and perhaps the indigenous tribes that roamed Eastern Europe millennia ago: One act of violence takes four generations to heal. One may choose violence when there seems no other way, but not without understanding the cost. It is the very opposite of the modern idea that violence ends violence.

It occurs to me that the superimposition of Marxism only brought another layer of forgetfulness of indigenous values. Marx and Engels may have been inspired by the “primitive communism” of the Iroquois Confederacy, but they ignored the principle that violence was likely to create more violence, that the means dictate the ends. Indeed, they preached the contrary: The end justifies the means. Marxism used all the worthwhile goals of indigenous life to justify almost any means. In a way, this is also the opposite of the logic of the Good Mind that Audrey Shenandoah explains in these pages. It justifies the negative and angry mind.

From this I learn the danger of all who would appropriate Native life: Lifting an element of The Way from its lived context can be a risky thing.

It is the mid-1990s, and I've been asked to speak about cooperative classroom styles that are helping girls learn and providing alternatives to competition for some boys, too. The occasion is a national conference of Native American educators who use Native history to teach engineering, chemistry, astronomy, mathematics, and other fields-areas that Native students are otherwise made to feel they do not “own.” I'm going on faith because Wilma suggested it, and because she will be speaking, too.

I'm to be met at the airport in Detroit, but I see no one except a heavyset man in a windbreaker who is leaning against the wall. He doesn't move in my direction. When no one else shows up, I ask if he is waiting for me-and he is.

I make small talk in the car by asking what he does for this huge conference. He says mildly that he is the head of it. He would have been content to continue being the driver if I hadn't asked; so much for hierarchy. As we pass a turn-off sign that says “Serpent Mound,” I ask what it is. Instead of being surprised that I, who grew up in this area, don't know, he just explains that it is an important example of hundreds of indigenous earthworks scattered across this subcontinent. They testify to the burial customs, astronomical knowledge, and lifeways of cultures at least a millennia before Columbus and often contain tools and jewelry made of bones or stone sheathed in hammered copper, decorations studded with freshwater pearls, remnants of pottery, woven cloth, and objects that could only have come from faraway trade. Indeed, some of these mounds may have taken centuries to build-with thousands of pounds of earth moved to create them, and the resulting basins turned into lakes for fish hatcheries. Until fairly recently, many authorities assumed such earthworks could not have been created by ancestors of the “primitive” peoples on this subcontinent, thus one of the Lost Tribes of Israel must have lived here in prehistory. Indeed, Mormons are still teaching this.

“I have friends who went to see Stonehenge in England,” he says. “I asked them if they wouldn't like to see monuments here that are older and just as meaningful. They said no.”

That's it. Somehow this “no” combines with my own ignorance as it has come home to me over the last twenty years and becomes the last straw. While my host is still smiling with the irony of their response, I am feeling angrier and more impatient, as if such emotions have been piling up and are finally spilling over.

I promise myself that I will spend what I can of the rest of my life making up for this lack of a knowledge that we may be literally dying for: not only of those mound-builders, or the Midwest settlement the size of London before Columbus showed up, or the southwestern tribes whose cliff dwellings have only recently been seen from helicopters-but also the modern Native novelists and poets and filmmakers who create with the double vision of what is and what could be, the tribes fighting against methane extraction and nuclear waste to save their land and our environment, the urban centers and colleges where Native cultures flower in the midst of skyscrapers, the new hope of “re-tribalizing” in an age when technology allows people to gather without nationalism or hierarchy-and most of all, the chance to listen to the voices of indigenous women whose living version of The Way I have been glimpsing over three decades.

When I say this to Wilma, she smiles, as if I've arrived in a place she already knows. She has been planning to travel around the country, to talk with indigenous women leaders who are so busy holding the world together that they have little time to strengthen each other's spirits, and to create a conversation that will support them and pass their wisdom on.

That was a decade ago. This is the living conversation you hold in your hands.

At the beginning of this journey years ago, I came home from road trips and saw on the rocks over New York's Midtown Tunnel this huge graffiti: WHEELS OVER INDIAN TRAILS.

I loved these painted words because they made me think: Who had walked across this same island? Who had touched the same outcroppings of igneous rock? Who had crossed the same rivers and looked out from the same ocean shore? Who had lived on the land where my house is built over an underground river, at the edge of a timeless boulder that stretches all the way to the center of the island?

I came to call this vertical history more visceral, sensory, and anchored in the land than the horizontal version that disappears into the mists of time. Still, I assumed that “Indian trails” meant the past and “wheels” meant the present.

Now, I wonder if the writer of this graffiti meant something different. After all, trails and wheels cover the same land and could be guided by the same wisdom.

These lifeways could be the wheels that will carry us all.

Gloria Steinem

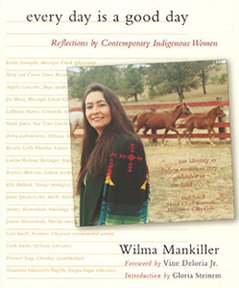

Text and cover image used with permission from

Every Day Is a Good Day: Reflections by Contemporary Indigenous Women by Wilma Mankiller © 2004.

Fulcrum Publishing, Inc., Golden, Colorado. All rights reserved.

|